It was a hot and sticky July day when I stepped off the Amtrak train in Baltimore’s Penn Station. I’d boarded an earlier train that day from Harrisburg to Philadelphia, driving to Harrisburg from Ithaca. The total transit time when driving vs. taking the train was about even, and the ability to get work done while traveling made the train a clear winner. I was in Baltimore for a series of Yankees vs. Orioles night baseball games, which gave me some time to explore the city during the day.

I was staying at the Hilton Baltimore Inner Harbor in a room overlooking the Seven Foot Knoll Lighthouse, which gave me the idea to spend a day exploring the holdings of the Historic Ships in Baltimore organization. My family took many trips on Amtrak from Metropark to Baltimore for Yankees vs. Orioles baseball games when I was a kid, but we only visited the ballpark and aquarium on our trips. I ended up visiting all the sites included with the $21.95 ticket: The Seven Foot Knoll Lighthouse, USS Taney, USS Torsk, US Lightship Chesapeake, and the USS Constellation. While I did visit the USS Constellation, I don’t really have any worthwhile pictures to share here besides the one above. Sailing ships aren’t really my thing, though I will say it’s evidently the most well-maintained ship in the fleet and quite unique as a museum ship.

USS TANEY

The largest ship in the museum’s collection, the USS Taney (WHEC-37), is a WWII-era Coast Guard cutter which served from 1936 until 1986. She witnessed the onset of US involvement in WWII while tied up at Pier 6 during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941. Among her duties in WWII was performing convoy escorts, shelling enemy positions on shore, and defending ships from kamikaze attacks. She is the last ship present at Pearl Harbor that’s still afloat today.

The single 5”/38 caliber gun mounted on Taney’s bow was her main offensive armament for most of her career; however, she did carry additional mounts during WWII. While the Navy was busy cramming anti-aircraft armament into every nook and cranny of its ships, the Taney was mounting additional 5”/38s. There are photos below-deck of Taney which provide a good representation of the many different configurations she sported during her career.

Taney served a very different role post-war, combating smuggling and conducting rescue missions on the open ocean. Her primary role was serving as an ocean station weather ship, reporting meteorological information that aided the preparation of weather forecasts.

Stepping aboard Taney rockets you straight back to WWII with that “old ship smell.” If you’re a fan of museum ships like I am, then you know what I’m talking about—that combination of old machine oil, paint, and general mustiness found aboard old ships. The tour route snakes along the top deck of the ship and down into the hull, giving you a peek at the engineering spaces, mess deck, and finally the 5”/38 mounted on the forward deck.

Having wood decking topside really does make a difference when it comes to the temperature below deck. Taney’s deck is stripped down to the steel underneath, and the spaces below are swelteringly hot. The Battleship New Jersey recently had her teak wood deck replaced at a cost of around $4 million, so I understand why the foundation chose to leave Taney’s deck bare. Caring for four vessels can’t be cheap, but without HVAC, the second deck basically becomes an oven. You could feel the heat radiating off the deck above the officer’s staterooms.

USS Torsk

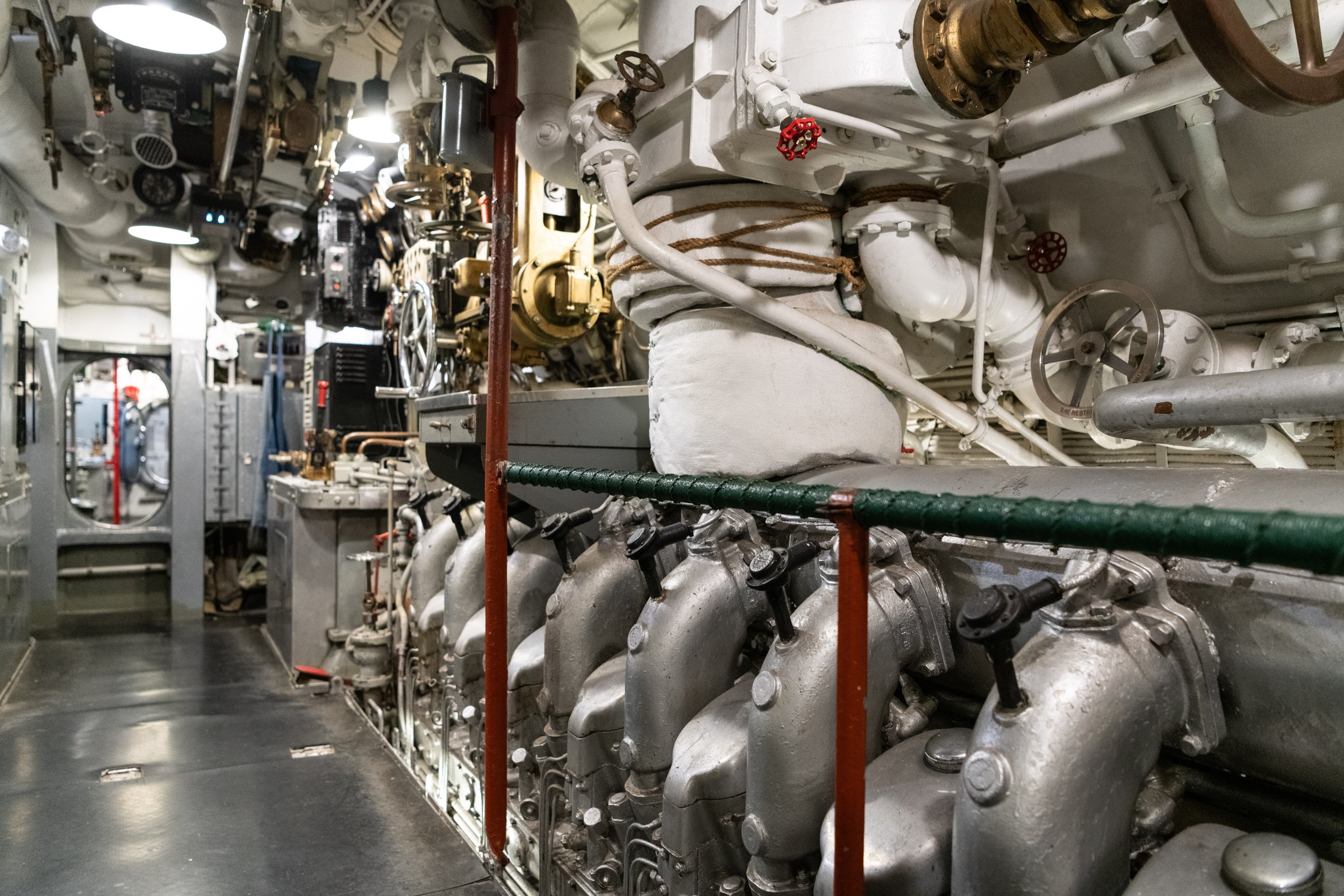

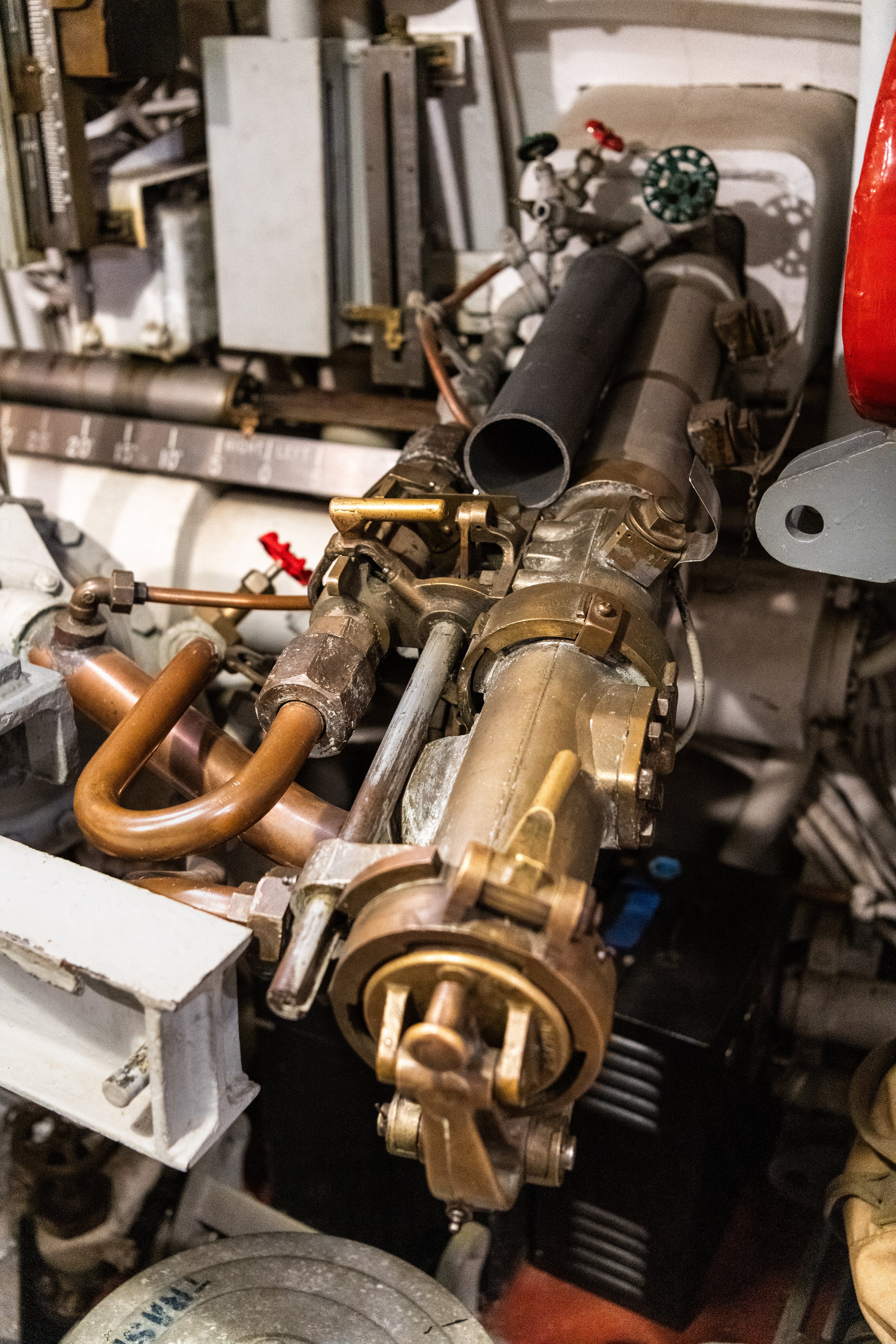

Next up was the USS Torsk, a Tench-class submarine docked right next to the Baltimore Aquarium. Torsk has the distinction of being the last US Navy ship to sink an enemy vessel during WWII. Her design was an incremental improvement over the Gato and Balao-class boats built earlier in WWII, and consequently, she only undertook two war patrols before the Japanese surrendered on August 15, 1945. After the war, she served as a training ship and anti-submarine training target until her decommissioning in 1971.

The Tench-class boats like Torsk were in an awkward position after WWII, having been made obsolete by advances in German U-Boat technology. A variety of programs were undertaken to extend the service life of these submarines, and the Torsk was converted under the “Fleet Snorkel” program. The sail was streamlined, and a snorkel system was added, allowing the operation of her diesel engines while submerged. The limited submerged range of her Sargo batteries could now be supplemented with diesel power if she could stay within snorkel depth when underway.

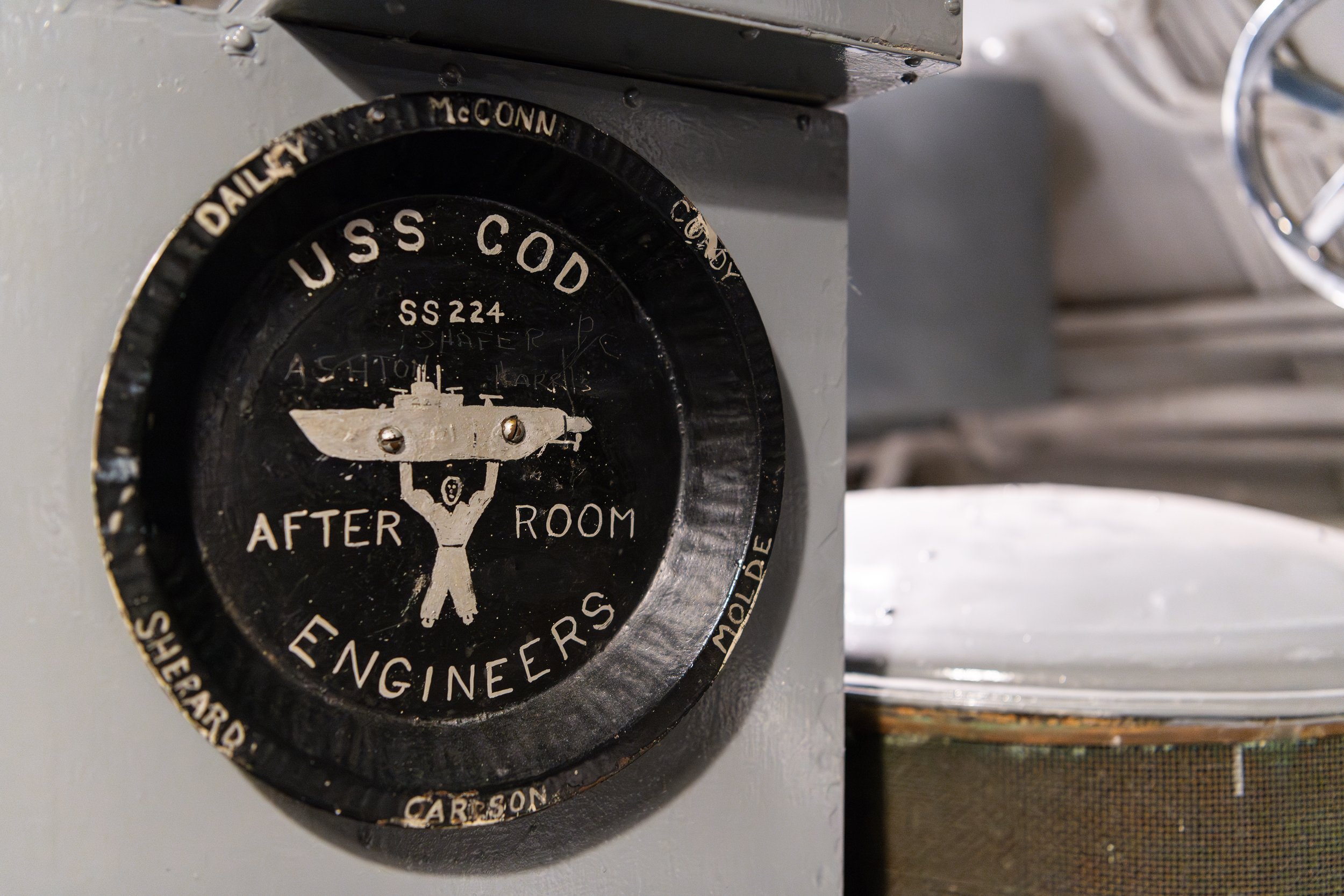

A little-known fact about the Torsk, like the USS Cod in Cleveland, OH, is that the only sailors lost during the boat’s history were a result of accidental overboard incidents. Joseph Grant Snow was lost overboard during a training dive on January 4, 1945, in the Atlantic Ocean. Snow was acting as a lookout on the bridge but did not make it down to the conning tower before the hatch was closed. His position on the dive planes at battle stations was covered by another crew member, and his absence was not noticed until the evening. His body was never recovered, considered lost at sea. An investigation into the accident led to the conclusion that new boats should not try to dive within the standard diving time until the crew has been thoroughly drilled.

Lightship CHESAPEAKE

Forward of USS Torsk is the United States Lightship Chesapeake. Built in 1930, she served multiple stations throughout her career until decommissioning in 1970. The primary function of a lightship was similar to a manned lighthouse - to provide a navigational aid to shipping. Lightships of the Chesapeake’s class feature two 5000 lb. mushroom anchors to hold the boat on station in all types of weather. Other features included a 13,000 candlepower beacon lamp, foghorn, radio beacon, and the name of its station stenciled prominently in white against the red hull for navigational purposes. Accommodations for the crew were spacious, with enlisted men sleeping two to a stateroom while officers had their own staterooms.

During WWII, the ship was painted haze gray, armed with 20mm cannons, and tasked with inspecting shipping headed for the Cape Cod Canal. This is the only ship in the Historic Ships in Baltimore collection which has any form of air conditioning, meaning I took a bit longer to explore this ship than I otherwise would have…

Seven Foot Knoll Lighthouse

Seven Foot Knoll Lighthouse is what I believe to be the most unique object of the Historic Ships in Baltimore collection. It is the oldest surviving screw-pile lighthouse in the world, built as a navigational aid to the Chesapeake Bay. The innovative feature behind the lighthouse was its screw-pile design, which allowed the piles to be screwed into the soft ocean bed and eliminated the complexity and expense of a masonry foundation. The lighthouse was installed in 1856. Keepers of the lighthouse would live in the structure with their families until 1919 when the keepers switched to working in pairs. Some lighthouse keepers even raised goats on the galley deck below the main living quarters! Lighthouse keepers were tasked with maintaining the 4th order Fresnel lens, which could be seen for 12 miles. The lighthouse was automated in 1949 and had fallen into disrepair by the time the Coast Guard donated it to the City of Baltimore in 1989.