My relationship with The Ridges, formerly the Athens Lunatic Asylum, began back in 2014 when I was a freshman at Ohio University. It was the start of the 4 years I’d live in Athens while working towards by BBA in Management Information Systems & Analytics at Ohio University. It was a chilly fall night and I was sitting in the lobby of Reed Hall (the same dorm my where my dad lived in 1980) with my friends when I first heard about the place - an abandoned asylum that sat atop a hill overlooking the South Green section of campus. A group of about 15 of us decided to brave the cold October weather and venture out into the night.

A winding road paved with ubiquitous “Athens Block” bricks leads you up to the rear of the asylum, a short walk across the Hocking River from East Green where I lived. Rusted iron fire escapes, tattered curtains slung behind barred windows, and a graveyard with almost 2,000 nondescript burials draped in darkness piqued my interests in history and architecture. I hadn’t yet discovered my love for photography, but The Ridges had me hooked on asylums. I spent lots of time walking laps around the former Kirkbride Plan asylum, mostly at night when I had free time after classes. Looking back on the very first pictures I shot with my D5500, I’m almost glad I never did any serious shooting there. I feel like I’d be disappointed looking back on those photos today. When my dad asked if I’d like to come along for a quick trip to Athens I jumped on the opportunity, excited to finally document the place where you might say it all began - the Athens Lunatic Asylum.

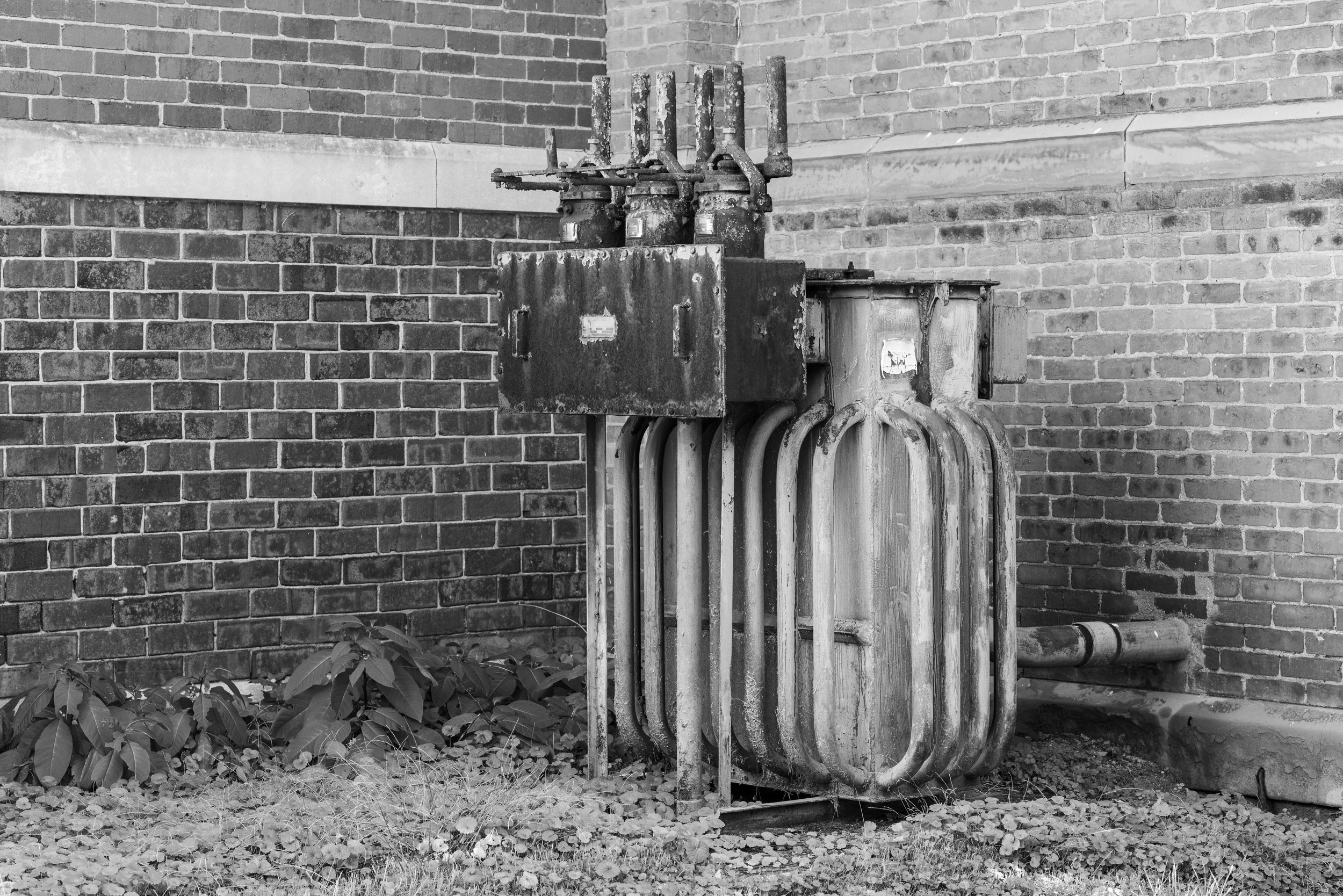

Opened in 1874, the Athens Lunatic Asylum was designed to house a combined total of 572 male and female patients. The campus was expanded over the years with new buildings and housed 1,800 patients at its peak in the 1950s. Ailments of those committed ranged form epilepsy to feebleness and hysteria. Physical labor was considered a form of occupational therapy, and patients helped staff the various agricultural ventures of the asylum. The entire campus was designed to be somewhat self-sustaining in nature, with a dairy barn, farmland, a power and steam plant, a piggery, and orchards. With the introduction of new psychiatric treatments and changes in the way mental illness was treated, the population of patients at the asylum steadily declined until the facility closed in 1993.

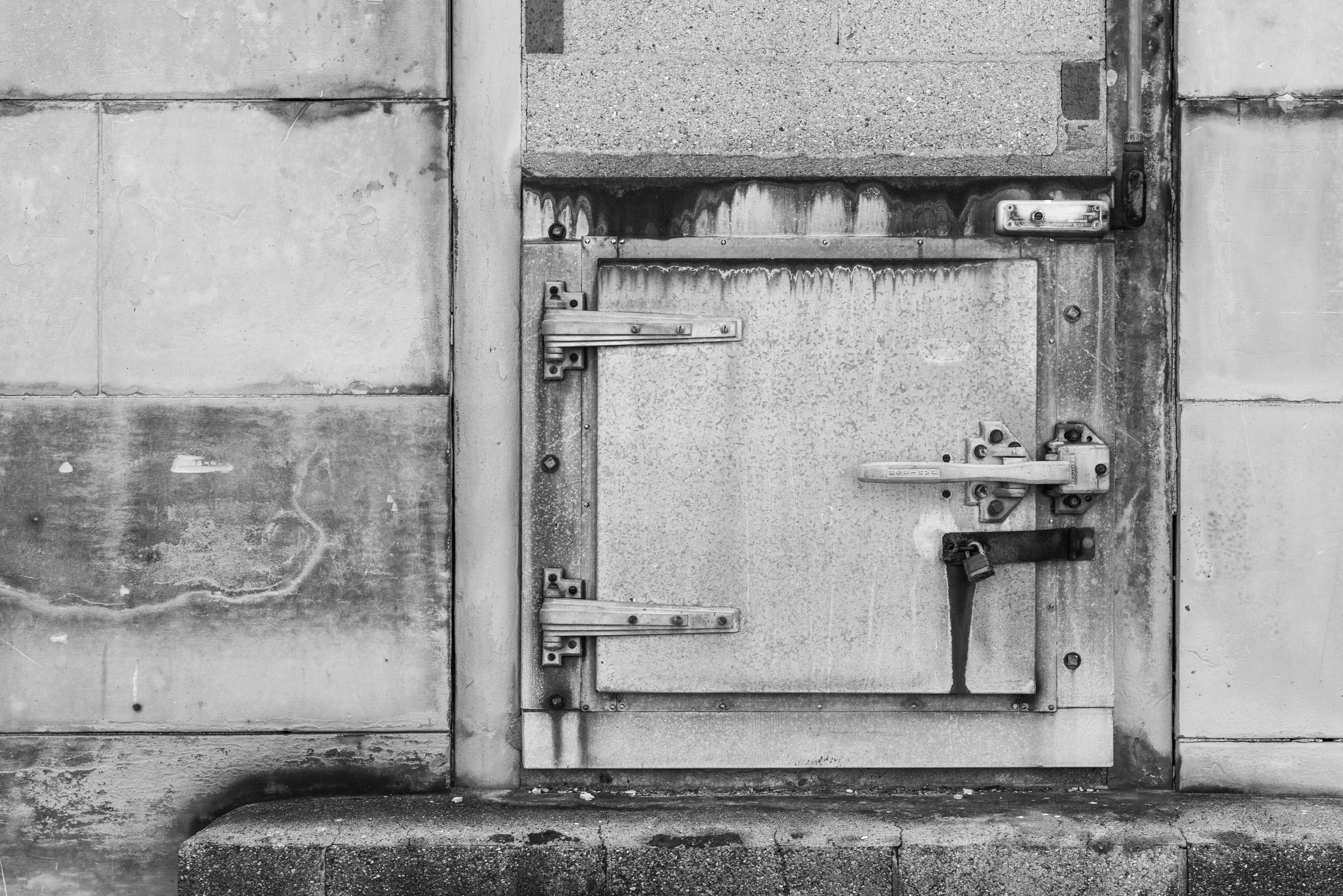

The Ridges are a rare case of an asylum finding new life after the deinstitutionalization movement and state governments sapped funding from residential mental health facilities across the country in the 1980s. Ohio University inherited the dilapidated complex of buildings in 1993, which had fallen into disuse as the patient census declined. The main Kirkbride building has been repurposed to host various functions of the university, including the police department and the Kennedy Museum of Art. The West wing, at least from the exterior, appears unused. The spires which dotted the roofline have been removed. A number of outlying buildings, including the receiving hospital, Cottage B, and the tuberculous ward have been demolished. Most later additions like the auditorium and cottages (excluding Cottage M which awaits asbestos remediation) have been remodeled and repurposed, presumably because the cost of renovation was more reasonable than the work needed to bring the Kirkbride building back online.

Over the years, around 2,000 patients were buried across the three cemeteries at The Ridges. Most were given numbered grave markers for which the ledger that contains personal details of those interred is long lost. Similar to Letchworth Village, numbered grave stones were used as a cost saving measure over creating custom marble monuments for the deceased. While The Ridges certainly gave off a creepy atmosphere when I first visited, I became more comfortable there during my many subsequent nighttime visits. I don’t particularly believe or disbelieve in ghosts, but I never saw much at The Ridges to make me think they exist. For me, The Ridges was a place to explore and unwind with a long walk at the end of a tough day. The familiarity of the towering asylum was comforting, almost like visiting an old friend. And I’m glad I made the trip.