One of Battery David Hunter’s empty 12-inch disappearing gun mount, Harbor Entrance Control Post (HECP) in background.

I’m always on the lookout for abandoned sites to explore, and I discovered Fort Start while looking for things to shoot in the Portsmouth NH area. This fort was part of a greater network of seven forts that protected Portsmouth Harbor, home to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. The port played a vital role throughout WWI and WWII, servicing the Navy’s submarine fleet. The shipyard continues to be the primary location for the overhaul, repair, and modernization of the active duty submarines.

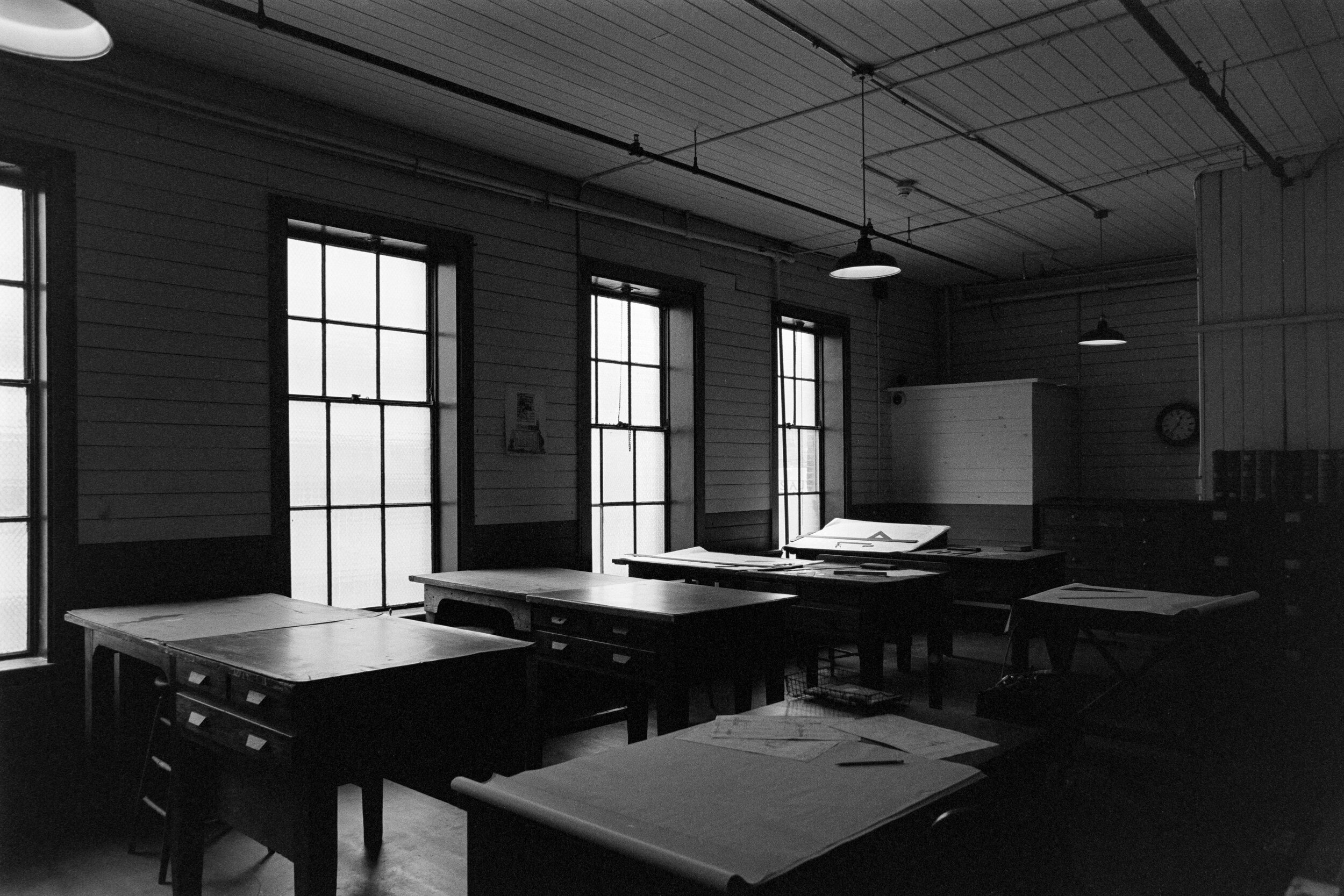

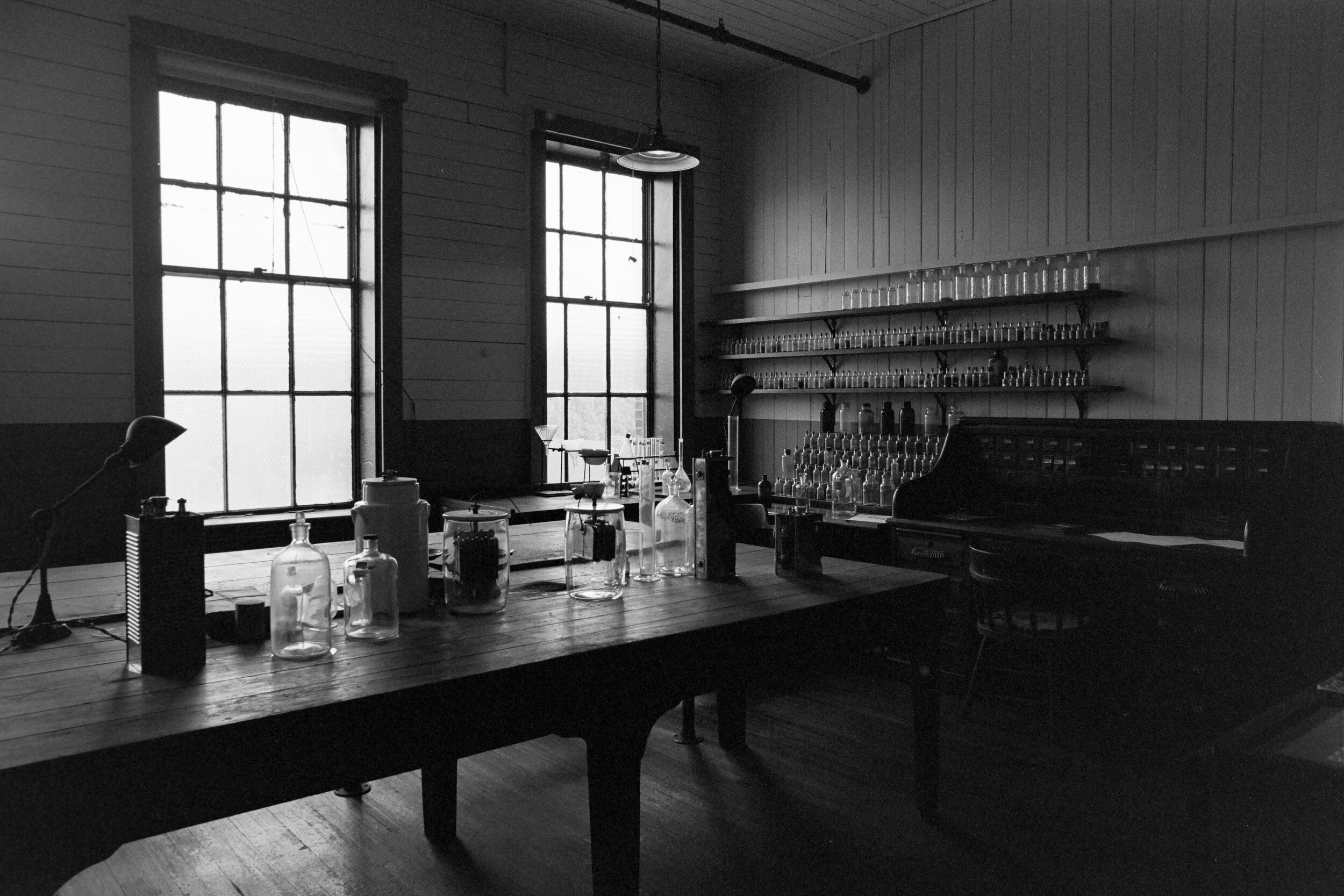

The fort was first established during the Revolutionary War, with armaments secured from the nearby Fort William and Mary after capture from British forces. The fort continued to serve a role in harbor defense up until 1983 when it was turned over to the State of New Hampshire. As it stood during WWII, there were 4 batteries: Alexander Hays, Edward Kirk, David Hunter, and William Lytle. A mix of 3-inch guns and two 12-inch guns (long since removed) made up the primary firepower and were eventually outclassed by the 16-inch guns of nearby Fort Dearborn. The main feature of the fort was the Harbor Entrance Control Post (HECP) which directed harbor defenses from Biddeford, ME to Cape Ann, MA. A collection of other buildings, none of which remain, surrounded the parade field to serve the needs of soldiers stationed there during WWII. Only the concrete bunkers and machine shop still stand, the latter converted to a small museum.

12-inch Gun Mount at Battery Hunter, showing the rails upon which the gun carriage would ride.

Walking through the remaining concrete bunkers, it’s easy to get a sense of the sheer scale of the 12-inch guns that once sat atop Battery David Hunter. These guns were never fired at the enemy, but were primarily a deterrent to minesweepers that might try to clear the main protective measure in place at Portsmouth Harbor – a vast minefield that was controlled from Fort Stark. The HPEC still sits atop Battery Kirk, which was painted “battleship gray” during WWII to disguise it from enemy observation. Other buildings at the fort were masked by camouflage netting supported by telephone poles.

While I was unable to visit the museum at the park due to COVID-19 restrictions, I was able to pop my head inside and take a brief look around. The one remaining 3-inch gun, an original search light, and other artifacts from the fort can be found inside. It doesn’t take much time to lap the entire park, but it’s fun to climb around the concrete bunkers and imagine what life was like for the soldiers stationed there. The park has limited hours and parking is only available past the entrance gate, but is worth a visit if you’re in the area.

A 3-inch gun mount added during WWII slides toward the ocean.