Whether I’m shooting digital or film, contact sheets are an important part of my editorial process. Taking pictures is only the first step in creating a new project: developing, researching, and editorializing all contribute to the final presentation of my work. While the workflow itself differs slightly when I’m working with film or digital, contact sheets are my favorite way to curate and annotate my photographs.

When it comes to the darkroom, contact sheets play a key role in determining what photos are worth printing. By exposing a sleeve of cut negatives directly onto photo paper, the photographer can view positives of an entire 35mm roll on a single sheet of 8x10 paper. Every enlargement costs materials and time to print, dry, and spot the final product. Contact sheets help the photographer craft their story and determine what photos are worth enlarging. The book “Magnum Contact Sheets”, which I reference frequently, gives a fascinating look into the mind and process of famous photographers like Robert Capa and Elliot Erwitt. The book shows contact sheets of Capa’s famous D-Day photographs and Erwitt’s capture of the “Kitchen Debate” between Nixon and Khrushchev, among many other famous photographs. I haven’t printed in the darkroom since college, but I still print digital contact sheets with my Canon PRO-100 at home.

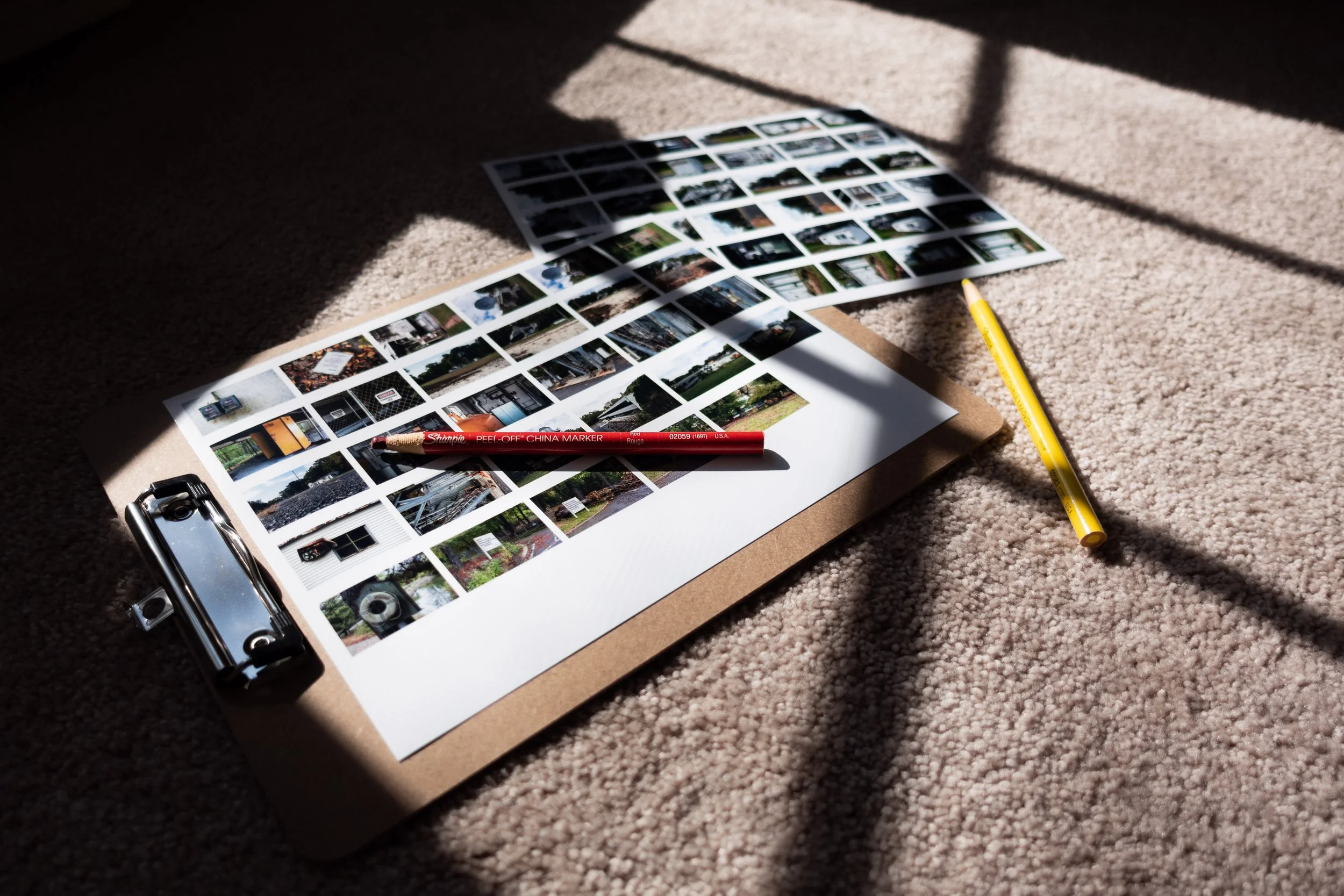

The process begins in Lightroom where I import my pictures for the first round of review, immediately rejecting any photos with glaringly obvious errors like terrible lighting, poor framing, camera shake, or missed focus. I then start tweaking the development settings of the remaining photos, getting them to a point where I can print a contact sheet. I have two different Lightroom preset that print 5x7 (35mm) or 3x4 (6x6) contact sheets on 8x10 paper, which I then review and annotate with grease pencil. I like Sharpie China Markers, red for color photographs or yellow/white for black & white.

The scans below are of some contact sheets I printed for the blog post I put together on The Holmdel Horn Antenna shot on my RX100VA - a box denotes a favorite, x a reject, and just the corners a crop. I’ve found that printing contact sheets and looking at them over multiple days helps me visualize the story I want to tell, weave my photographs into a cohesive narrative, and be more critical of my work. After I finish annotating a contact sheet, I’ll use it as a reference to construct the webpage layout and make any final edits to my images. I think there’s something about physically printing and annotating your photos by hand that will help you see them in a whole new light - give it a try!