Just to the West of San Diego International Airport was once a large US Naval Training Center named Naval Training Station San Diego, known today post-redevelopment as Liberty Station. Scrolling over a satellite view of the formal naval base, one peculiar structure sticks out - what looks to be a Navy ship, somehow sailing on land? Affectionately nicknamed the USS Neversail for its lack of propeller or driveshaft, USS Recruit was built at the tail end of WWII to train recruits on naval customs and tradition before they set sail on a real ship. Commissioned, decommissioned, and recommissioned in 1982, TDE-1 USS Recruit had a hand in the training of naval recruits from WWII through the Gulf War, serving until Naval Training Station San Diego’s closure in 1997.

I was surprised by just how large the ship is when I walked alongside it. Originally designed as a 2/3 scale model of a WWII destroyer escort, she was reconfigured in 1982 as an Oliver Hazard Perry class frigate. This added the requisite CAS antenna and single OTO Melara 76 mm gun mounted forward which can still be viewed today. I can’t say I’ve ever walked alongside a real US Navy frigate before, but I can easily imagine just how large they are based on this model.

Believe it or not, the USS Recruit wasn’t the Navy’s first attempt at a land-bound ship. The first USS Recruit was constructed in 1917 in New York City’s Union Square as a recruiting tool to drum up enlistments for WWI. A fully rigged battleship, the original USS Recruit helped bring 25,000 sailors to the war effort. The 1917 USS Recruit featured a full compliment of six 14-inch guns and ten 5-inch casemate guns, all recreated from wood. Another landlocked ship, the USS Trayer, is still in use at Recruit Training Command on the Great Lakes in Illinois.

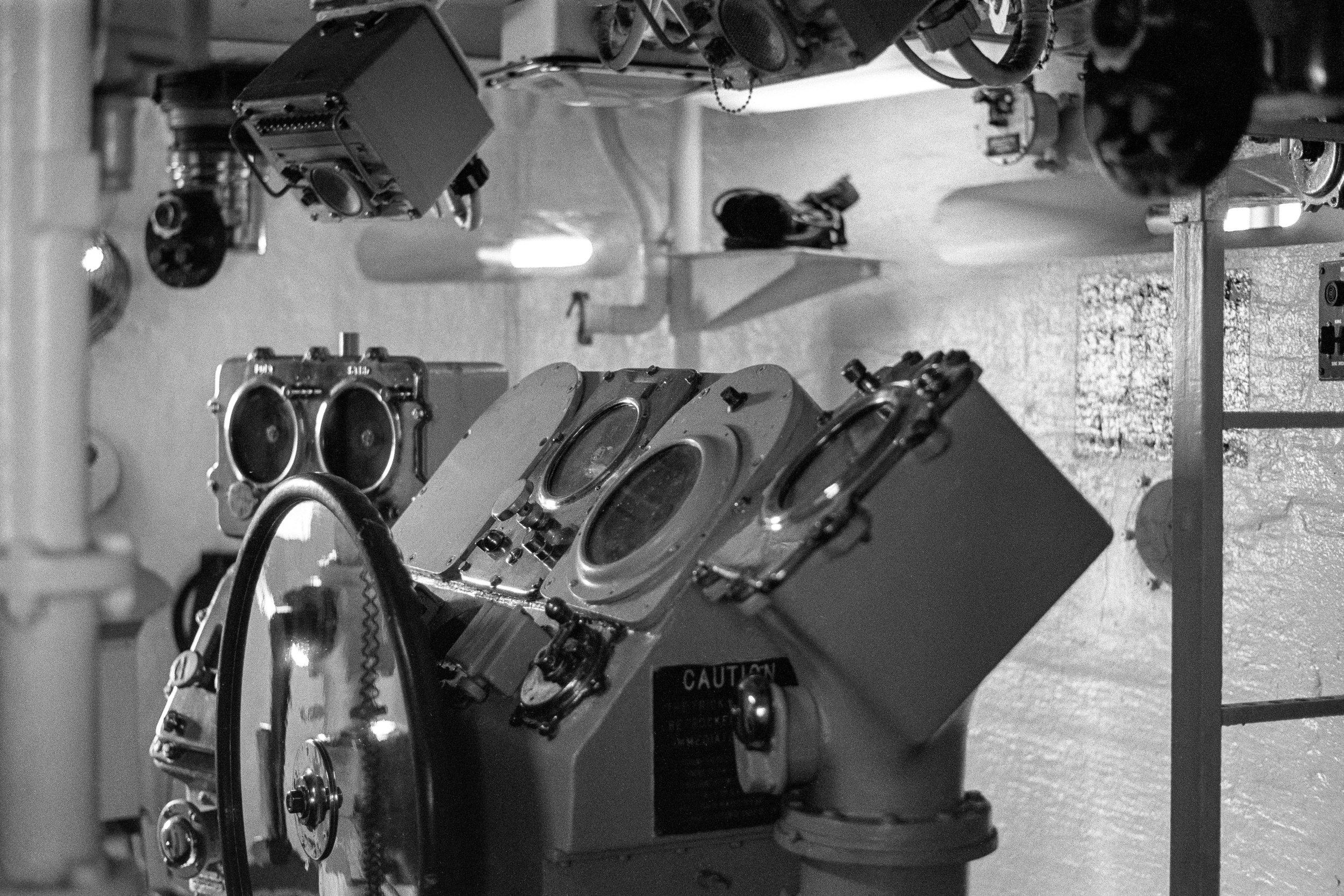

From afar, the starboard side of the ship looks pretty convincing if you can ignore the fact it isn’t afloat! The port side of the ship reveals USS Recruit’s dual purpose as a classroom and model, as six sets of doors are cut into the hull for ease of entry. Within the windowless hull were six classrooms to compliment the array of naval equipment used to train recruits topside. The little details like anchors, hatches, and radar equipment on the mast all match what you’d expect to see if you were sailing the high seas on a ship like the USS Samuel B. Roberts, another Oliver Hazard Perry class frigate. The ship remains in stasis today, maintained but not open to visitors. The USS Midway Museum is involved in the maintenance of the ship, and the landscaping which surrounds it is very well-kept. There isn’t an immediate plan to open the ship to tours that I know of, so for now we’ll just have to be satisfied with admiring this naval oddity from the outside.